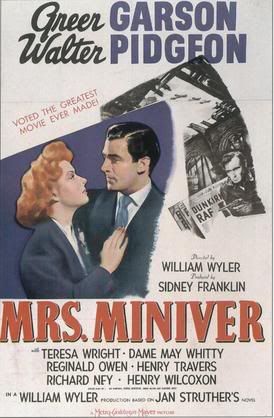

1942: Mrs. Miniver

Mrs. Miniver (Wyler, 1942) 6/10

"This is the People's War. It is our war. We are the fighters. Fight it then. Fight it with all that is in us and may God defend the Right" (Vicar)

"This is the People's War. It is our war. We are the fighters. Fight it then. Fight it with all that is in us and may God defend the Right" (Vicar)During the Second World War, American cinema played a crucial wartime role. At the front, motion pictures were used to entertain the troops; at home, films became important tools in providing information, influencing public debate and assuaging the masses. Perhaps no other film of this era did more to affect the general public than William Wyler's 1942 classic Mrs. Miniver.

Heralded by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill as being "more important to the war than the combined work of six divisions," Mrs. Miniver was both a monumental commercial and critical success: a polished archetype of 1940's MGM high drama that raked in over five million dollars and collected the Academy Award for Best Picture. Adapted from the short stories of English novelist Jan Struther, Wyler's inspirational melodrama focused on the war-time struggles of the film's titular "middle-class" heroine Kay Miniver played by Greer Garson.

Set during the first two years of the war, the film examines the changes affecting the Miniver household and their rural southwest England community. Prior to the war, the Minivers are portrayed as a typical, hard-working English "middle-class" family. The family patriarch Clem (Walter Pidgeon) is a successful architect, whilst their eldest son Vincent (Richard Ney) attends Oxford. Whenever the couple are not spending their "little money" on extravagant purchases behind each other's back, they are raising their two younger children: one of whom takes piano lessons, the other who is perpetually holding a kitten.

The onset of the war however threatens to destroy this bucolic splendor within the Miniver household. Whilst the conflict hampers Vincent's impulsive romantic pursuits of Carol (Teresa Wright), the socially conscious granddaughter of the town's lone aristocrat Lady Beldon (Dame May Whitty), it also deeply changes the community and its rigid class identities. This is most sharply evident in the conflict between the haughty Lady Beldon and Mr. Ballad (Henry Travers), the town's working-class stationmaster.

For over three decades Lady Beldon has won the grand prize at an annual flower show hosted on her property. When the meek Mr. Travers decides to enter his own rose into the competition, his audacious act is seen by Lady Beldon as a swipe against her rank in the community: threatening to jeopardize her status. Furthermore his decision to name the flower after Mrs.Miniver, rather than a lady of the gentry causes a stir throughout the town. These ideas soon become relics of the past. Within a matter of weeks, the war's arrival brings with it a minimization of class boundaries. The caste-like walls, previously unchecked only in the town's local pub, are torn down in the name of sacrifice and communal spirit.

The attempt to project the dissolution of class lines in Britain was one of the key driving forces in the film's production. At the behest of the American Office of War Information, MGM were asked to create a film that not only stressed the importance of communal togetherness during the war, but also projected a new image of Britain to American audiences detached from traditional Hollywood conceptions of Britain as a stuffy, anachronistic society. Wyler's film was meant to create a more democratic idea of Britain that could allow American audiences to sympathize with the plight of the British.

In its presentation, the film's contemplation of the British class system is severely flawed. In MGM's glamorized depiction of British "bourgeois" life, the Miniver family manages to maintain a spacious house located on the banks of the Thames equipped with a motorboat, two live-in servants and a luxury automobile. The Minivers and their fellow townspeople are deemed to be ordinary, everyday figures through this logic; despite the fact they- The Minivers- are clearly more privileged than their middle-class background suggests.

The village's working-class are easily identifiable through their colloquial accents and speech, yet are routinely characterized as almost childlike citizens who look up to the more adult and responsible bourgeois and aristocratic members of the community. There is little mention of the economic strife and class-orientated politics that affected Britain at the time. Rather this is a sanitized and wholly idealized image of Britain that continued to feed into popular, weatherworn images of people enjoying cups of tea or a rousing pint of bitter at the quaint local pub. Mrs. Miniver's Britain is a conservative one of stiff upper-lips and upper-crusts.

Nevertheless, by projecting an image of quotidian activities and individuals, Wyler's film managed to transcend international cultural boundaries. The film became important because it stressed the ideas of sacrifice, duty, solidarity and harmony. In this way it is easy to see both why U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked for the film to be rush-released and why the film itself became so popular. In an era when propaganda and jingoistic war films tended to focus on the battle front, Mrs. Miniver turned its lens toward the rarely analyzed home front. There despite their economic superficialities, the Miniver's struggles and strife became easily identifiable and therefore offered comfort and empathy to millions of viewers. The film's brilliant and rousing final speech delivered by the local Priest (Henry Wilcoxon) is a magnificent piece of inspirational screenwriting.

The film also provided a blueprint for how the citizen soldier should operate during war time. Although the film fails to address the true historical realities, which would have likely have seen both Clem and Kay Miniver holding voluntary positions to assist local war-time organizations, it does offer a moral layout of how they should act socially and politically. In Mrs. Miniver, dissension on the home front is non-existent. Everyone unquestionably acts without exception. Non-conformity or fear is invisible. Not only does everyone in Wyler's film participate in the war effort to the best of their abilities- forfeiting relationships and economic progress in the process,-but they further defy the war's horror by continuing to engage in regular activities. Thus, the film became an important political tool in providing an example of good conduct and citizenship for viewers, as well as emotional support and encouragement for millions of viewers.

Since its initial release in 1942, Wyler's film has lessened in stature. Its idealized view of British society appears dated and weather-worn. The film's soapy melodramatic narrative that once appeared honest and realistic, today appears long, contrived and ponderously slow. The film's glossy patriotism that once aroused and inspired audiences in particular feels naive and calculated. For the majority of Mrs. Miniver, the film's leading performances including Greer Garson's Oscar-winning effort as the title character loom as synthetic archetypes of cool, calm and collected citizenship.

With her expansive eyes and unflappable serenity, Garson's Miniver rarely comes across as genuine. As a result, the film's infamous scene in which Mrs. Miniver single-handedly combats the Nazi threat appears especially ludicrous. Walter Pidgeon's portrayal as Clem is stiff and nondescript. Despite appearing in several films together, Garson and Pidgeon lack any believable chemistry in Wyler's film. The only genuine romantic chemistry in the film awkwardly belongs to Garson and Richard Ney, who woodenly plays her garrulous son Vincent. Ironically, the pair dated during filming and were later married. Only Teresa Wright, as the fresh-faced Carol, Henry Wilcoxon as the motivational cleric and Henry Travers as the shy flower enthusiast seem to have injected any genuine spark and humanity into their performances.

Despite its slick, outmoded approach, there are still moments when Mrs. Miniver's polished artifice still manages to kindle something more than sentiment. Joseph Ruttenberg's cinematography, particularly in the film's climatic coda in the village church is especially rewarding. Packaging the film around a series of set-pieces, Wyler managed to extract some of the film's best performances during these segments. Scenes including those during an air raid and the film's finale added an element of authenticity and intrigue often absent in the film's fabricated projections.

Nevertheless, through its images and essence Mrs. Miniver became an important and immensely popular film, which spawned a far-less successful sequel, 1950's The Miniver Story. Four years after directing Mrs. Miniver, Wyler would helm a far more authentic and less idealistic conceptulization of the home front with his 1946 Academy Award winning film The Best Years of Our Lives.

* Mrs Miniver is available on DVD through Warner Home Video

Other William Wyler films reviewed:

The Letter (1940) 7/10

Copyright 2008 8½ Cinematheque

<< Home