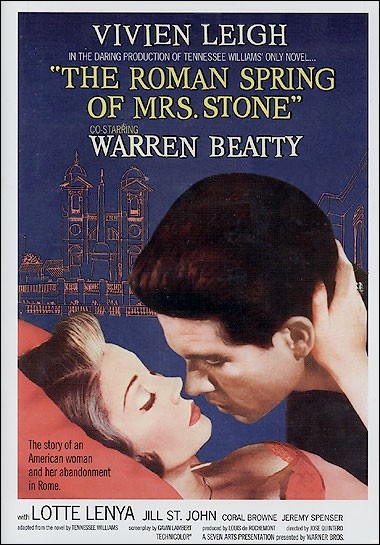

1961: The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone

The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone (Quintero, 1961) 6/10

Throughout the his illustrious career, the American playwright Tennessee Williams produced numerous plays and poems, but only a single novel:The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone. Adapted for the screen in 1961, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone marked the return of Vivien Leigh to films after a six-year absence.

Throughout the his illustrious career, the American playwright Tennessee Williams produced numerous plays and poems, but only a single novel:The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone. Adapted for the screen in 1961, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone marked the return of Vivien Leigh to films after a six-year absence. In her second-to-last project, Vivien Leigh plays Karen Stone: an aging New York stage actress, who flees to Rome with her ailing husband after receiving poor reviews as Rosalynde in Shakespeare's As You Like It. On their journey to Italy, tragedy strikes when Karen's frail husband abruptly dies onboard a Transatlantic flight. Unwilling to resurrect her career and unable to face her critics, Karen decides to reside permanently in Rome.

After a year hidden away in her spacious apartment, Karen is introduced to the manipulative Contessa (Lotta Lenya) in a bid to end her solitary life. Adorned in gaudy clothing, the Contessa is in actuality an upper-class pimp who operates a niche market; offering young men to lonely middle-aged women amongst Rome's wealthy American expatriates and native noblesse. Desperate to count the prosperous Mrs. Stone as a valued client, the Contessa pushes the selfish Paolo (Warren Beatty) on her. But when the proud former actresses senses fail to be initally aroused, Paolo and the Contessa begin to hatch their own schemes with volatile results.

Partially shot on location, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone is a flawed film, albeit one with a stimulating array of sub-texts. As with other Williams compositions, themes such as sexuality and youth play an integral role. From the film's first shot of Mrs. Stone's Roman enclave, illicit sex is found in abundance. Located adjacent to a series of notorious piazze, Mrs. Stone's living quarters are principally positioned at the epicentre for prostitution in Rome. Subsequently, when the Contessa champions the view from Karen's balcony, one wonders if she is referring to the historical sites or the physical sights below.

With her supercilious air and exultant manner, Mrs. Stone certainly represents one of Tennessee Williams chief thematic maxims as the moralistic individual who indulges in a covert lifestyle. Nevertheless, the presentation of this aspect of Mrs. Stone's life is particularly mystifying in Quintero's film. There is little inclination either through Gavin Lambert's script or Leigh's body language in the film's opening stages to explicating Karen's motivations or her erotic impulses. Rather, for the vast majority of The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone, Karen appears to be desperately seeking companionship of a platonic kind, which she can sadly only accrue through Beatty's local gigolo.

As demonstrated through her repeated glances in her mirror, Karen is beginning to feel her age. With his flirtatious gestures, Paolo certainly provides an element of flattery. Yet, throughout The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone there is little evidence that Karen really desires this type of intimacy. In one scene, Karen is described by a friend as a person eager to avoid love. The mere fact she has successfully holed up in her apartment for a year with scant social contact seems to suggest her character is content in her independence and introversion. Furthermore, the fact Karen has not explicitly ventured down to the piazze below to pick-up men indicates her lack of overt interest in sex. Thus, making her converted opinion of Paolo even more enigmatic.

Unlike Billy Wilder's Sunset Boulevard, which also features a relationship between an aging former star and an obnoxious young man, Quintero's film does not propagate the idea that his female protagonist is either saddened by her plight or desiring a younger lover. Rather, the film makes repeated assertions that Karen is not a forgotten figure in New York and that she has intentionally chosen to avoid her former friends and associates.

While the emotional stimuli and physical cravings of its characters are questionable, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone does offer some compelling sideshows. Like Federico Fellini's masterpiece La Dolce Vita released a year earlier, Quintero's film explores the seedy and decadent Roman underworld of the affluent. Additionally, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone does address celebrity culture, although not nearly to the extent analyzed in La Dolce Vita.

Arguably the most interesting aspect of The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone is the film's overall darkness. The maliciousness of its characters coupled with the film's sub-plot involving a stalker demonstrate a misanthropic outlook rarely addressed in American cinema during this period. The film's ambiguous finale is in particular especially bleak in its resolution.

Released in 1961, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone proved to be a critical and commercial disaster. Consequently, it became the only film ever assigned to experimental theater director Jose Quintero. Despite a subtle effort by Vivien Leigh and Lotta Lenya's twisted turn as the Contessa, most of the film's criticisms were directly attuned toward Warren Beatty's awkward performance as Paolo: a fact aggrandized by his errant faux Italian accent. Ever since its initial release, Beatty has somewhat unfairly continued to be earmarked as the film's achilles heel.

In actuality The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone is a film broken by its slow, suggestive script emphasizing scintillating sin, over plot and character development. The result is arguably the weakest of Hollywood's Tennessee Williams cycle during the Fifties and Sixties. Nevertheless with its dark moral corners, Herbert Smith's luscious art direction and Franz Waxman's fluid cinematography, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone does at times propose to be something more than a flat jaded tale of forlorn romance.

*The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone is released on DVD by Warner Home Video and is also available in their excellent Tennessee Williams Film Collection box set

Copyright 2008 8½ Cinematheque

<< Home