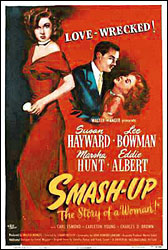

1947: Smash-Up

Smash-Up: The Story Of A Woman (Heisler, 1947) 4/10

In general studies of Hollywood history, Billy Wilder's 1945 film The Lost Weekend is often considered to be the first major Hollywood production to seriously tackle the destructive qualities associated with alcoholism. However, contrary to this popular opinion, Hollywood had previously explored this topic in films such as Victor Fleming's 1932 film The Wet Parade and Alfred Green's 1935 Bette Davis' vehicle Dangerous.

In general studies of Hollywood history, Billy Wilder's 1945 film The Lost Weekend is often considered to be the first major Hollywood production to seriously tackle the destructive qualities associated with alcoholism. However, contrary to this popular opinion, Hollywood had previously explored this topic in films such as Victor Fleming's 1932 film The Wet Parade and Alfred Green's 1935 Bette Davis' vehicle Dangerous.Yet, these socially conscious Prohibition-era dramas were rare instances of Hollywood's attempt to depict alcoholics as sick individuals, rather than jovial comedians in the vein of W.C. Fields. Following the release of Wilder's film for Paramount in 1945, Universal decided to tackle the subject through Stuart Heisler's 1947 film Smash-Up: The Story Of A Woman.

Often unfairly referred to as a female version of The Lost Weekend, Heisler's film starring über-melodramatic actress Susan Hayward eliminates the rough, realistic interiors of Wilder's film and adds a glamourous sheen noted in Stanley Cortez's polished cinematography. Hayward stars as Angie Evans, a nightclub star who abandons her career after settling down with aspiring radio crooner Ken Conway (Lee Bowman).

While Evans at first dutifully aids her husband's career, she sinks into a depression once Ken's career begins to skyrocket. Finding comfort in the bottom of a bottle, Evans starts to suspect her husband is cheating on her with his dull assistant Martha (Marsha Hunt) and acts outwardly under the influence to project these claims. Repulsed by her behaviour, Ken begins divorce proceedings, while the reckless Angie attempts to solder together the twisted and tattered remains of her life.

Smash-Up: The Story Of A Woman is a tawdry melodrama clothed in glittering gowns and rested in satin sheets. Set in high-rise luxury apartments, Heisler's film presents itself as an exposé of alcoholism as a classless disease. Living in their art-deco apartment, Angie lives amongst an abudance of luxury items. Yet, this cannot compensate for her sense of isolation, envy and mistrust. Despite, Ken's attempts to provide his wife with all her material desires, they do not substitute for the increasing absence of love within their marriage.

Juxtaposing his two central characters, Heisler creates a pictoral diagram that correspondingly shows the couple's careers and personal feelings always flowing in opposite directions. As the film flashbacks to our first meeting with Angie, we see through Heisler's efficient montage the rising spectre of her career, as she elevates to bigger and better clubs. Her reunion with her impovershed lover Ken notably demonstrates her willingness to submit to his charms. The first time Heisler reveals their relationship to the audience, it is noticeable that Angie immediately leaves the club to go home with Ken and that Ken is unable to afford the cab fare: perhaps illustrating a relationship based on physicality rather than true emotional connections.

Performing an array of flat Country and Western songs with his writing partner Steve Anderson (Eddie Albert), Ken elevates his career by singing standards attuned to his voice at Angie's suggestion. Thus, begins the accleration of Ken's career and the declination of Angie's. Staying at home to tender to their newborn child, Angie abandons her successful career in order to aid in the launch of Ken's stalled fortunes. In Hayward's character one therefore sees a foreshadowing of the sense of disillusionment which simmered under the surface of 1950's American culture. There, housewives forced out of their wartime jobs were often relegated to suburban estates planted on empty rural lots and expected to happily deploy their maternal instincts.

Like Angie, thousands of women turned to legalized narcotics and alcohol in order to stifle their bouts of depression. Ken's inability to emotionally assist his wife is symptomatic of an entire culture during the Eisenhower era; predicting the rise of a generation of men equipped with the mental tools of war, yet unable to deal with the emotional necessities of the post-war domestic front. While the social dilemmas of the post-war middle class would later be decadently exploited by German emigré Douglas Sirk in films such as Written On The Wind and All That Heaven Allows, Heisler's film is fixated on the nouveau riche. And thus with household staff attending to her and child's every need, Angie's desire to be a housewife is undercut by her false desire to attend to such matters and the superfluous nature of her staying at home.

With its extravagant mis-en-scene and its soapy plot, Smash-Up feels visually inequipped to deal with the Noirish undertones Cortez occasionally imbues onto the screen. Instead his swirling photography impassively projects an image of an extended bad dream: a concept resonated in the film's opening scene of a maimed Angie awaking from anaesthetic. Heisler's repeated use of Angie slurringly waking after another blackout, also heightens the notion that the Conway's glossy reality has been broken by her nightmarish drinking. Yet, Angie's scuttling attempts to piece together the past posits her as a Noir-like amnesiac: utilizing the fragmented clues to piece together a mental jigsaw.

Hayward's character is indelibly interesting as that she is permanently flawed. Lacking in self-confidence even prior to Ken's success, she often uses alcohol simply to garner the courage to perform onstage. The incessant clamouring for attention from female fans and Martha's adulterous overtures accelerate her alcohol intake. Such is her lack of faith in her abilities, her attempts to motivate herself to reclaim her family are crippled by her necessity for the bottle. This produces a lifestyle as deceptive as the lavish high-rise apartment she lives in.

Drowning her sorrows in whiskey, Angie becomes a self-destructive figure: one which Heisler proposes it both perpetrator and victim of her own folly. With Hayward's excessively histronic performance at the forefront, Heisler shows his protagonist as a femme fatale debilitated by her need for alcohol. With her wild accusations and vile behaviour, Angie becomes a malevolent figure destroying- to an extent- the lives of those around her. Yet, within the classic contours of the Hollywood melodrama, she is grafted an opportunity to redeem herself and thus repair the damage.

As a victim, on the other hand, Heisler shows the neglect of her absent-minded husband which seemingly drives her into a state. The miscast Lee Bowman simply adorns her with shimmering gowns, pearls and all the trappings of luxury in order to compensate for his absence and for the paucity of their early relationship. Yet, Heisler undercuts this notion by demonstrating the innate weakness of his protagonist from the beginning. Furthermore, the hyperactive nature of Hayward's performance necessitates Bowman to either play his character as a weak man or an equally aggressive figure. Instead he exudes the essence of a befuddled fall guy: unsure as to how he acheived fame and unwilling to associate with anyone else in the film.

Furthermore, unlike in Wilder's film, Smash-Up fails to capture the pure sense of desperation and helplessness conveyed in The Lost Weekend. While Wilder had Ray Milland suspensefully hide a bottle outside an apartment window, Heisler has Susan Hayward bemusingly searching for sugar in kitchen cabinets overflowing with booze. The subtle nature of Wilder's film is absent in Smash-Up: producing a schizophrenic picture brimming with Noirish conflict, but packaging its appearance in silk clothing and its outcome in bittersweet perversity.

Smash-Up: The Story Of A Woman is a prospectively interesting, but ultimately stolid film. With its myriad of hints at devious and illicit behaviour, the picture could easily have been crafted into a sultry Noir or a dirty seething melodrama: with an actress like Joan Crawford or Bette Davis aggressively contesting her fondness for drink, or perhaps Olivia de Havilland or Joan Fontaine engaging in clandestine binges. Heisler's film is somewhere in the middle. Its slow-baked pacing and aesthetic sheen are sub-MGM, but Hayward's performance is unmatched by her fellow cast members: allowing for the film to dither intoxicatingly into stagnation.

* Smash-Up: The Story Of A Woman is available on countless Public Domain DVDs

Copyright 2007 8½ Cinematheque

<< Home