1952/1995:Othello

Othello (Welles, 1952) 6/10

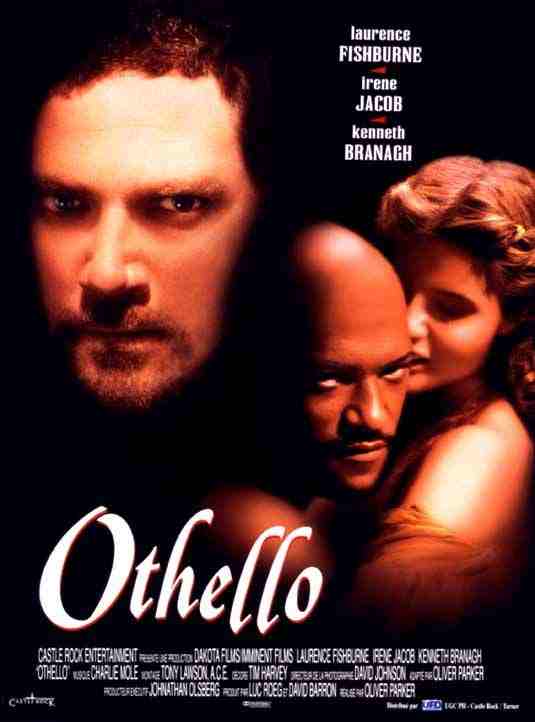

Othello (Parker, 1995) 7/10

William Shakespeare's early 17th century play Othello has been approached by scholars and critics as a meditation on several topics included race, jealousy, power and sexuality. On celluloid, these themes have been amplified, distorted and removed: creating a flurry of different takes on Shakespere's Mediterrenean domestic tragedy featuring thespians such as Laurence Olivier, Orson Welles, Emil Jannings and Laurence Fishburne in the title role.

There have been over a dozen adaptations of Othello filmed in countries ranging from Italy, the Soviet Union and Weimar Germany; utilizing the methods of silent cinema, Noir or re-invisioning the piece as a high school melodrama. Two of the most notable cinematic adaptations of Othello are the 1952 Palme d'Or winning version from Orson Welles and 1995's Oliver Parker adaptation: often commonly and mistakenly attributed to Kenneth Branagh.

In both films, the basic tenants of the Othello tragedy are told. Othello, a General working for the Venetian army secretly elopes with Desdemona. The marriage is a highly-contested affair. Scholars dispute whether Othello's status as a Moor signifies him as being of black or Middle Eastern descent, or simple a Muslim. However, in most cinematic readings of the play, the title character has been portrayed by a black actor or a white actor in dark make-up.

In both films, the basic tenants of the Othello tragedy are told. Othello, a General working for the Venetian army secretly elopes with Desdemona. The marriage is a highly-contested affair. Scholars dispute whether Othello's status as a Moor signifies him as being of black or Middle Eastern descent, or simple a Muslim. However, in most cinematic readings of the play, the title character has been portrayed by a black actor or a white actor in dark make-up. Such is Othello's status in Venice, that the marriage is allowed to continue and Othello goes to Cyprus to defend the island against the invading Turkish forces.Before Othello leaves Venice he names Cassio as his lieutenant: a decision which angers his ensign Iago who embarks on a course of revenge. Playing upon Othello's natural instability and jealous disposition, Iago craftily manages to convince Othello that Desdemona is engaged in an adulterous affair with Cassio: resulting in a tragic and blood-strewn finale.

Filmed on and off over the course of three years, Orson Welles' low-budget adaptation of Othello is a dark Expressionistic jumble. Due to the director's problems financing the picture, Welles would often resort to appearing in films such as The Third Man during filming; only to return later and have to hire new cast members as previous ones were forced to drop out due to other commitments. The result is a jagged and chaotic jumble of ideas and images: a "grand folly" in the words of critic Peter Travers.

Certainly, Travers' words and the assertions of Roger Ebert hold a degree of truth. In spite of a well-documented restoration, Welles' film suffers from a degree of problems pertaining to its messy history. Scenes shot in Morocco would have to be connected to those shot in Venice. The awkward nature of this process is evident in the repeated shots that fail to match. The film's rapid-fire editing and post-production dubbing is also unwieldy: overcomplicating one of the paciest adaptations of Shakespeare on screen.

Parker's film on the other hand is a slick mainstream piece, owing more to the hyperactive nature of Kenneth Branagh's Iago than hyper-kinetic visuals. Featuring a notable cast, Parker's film carries more brand name baggage than Welles' poverty row approximation. Yet, this does not necessarily equate to greatness. Like Welles, Laurence Fisburne seems miscast in the title role. While Welles is often a heavy capricious ham, Fisburne arrogantly scowls rather than broods in a role he never appears comfortable within.

Equally miscast is the role of Desdemona in each film. Suzanne Cloutier's limitations in Welles' version are inhibited by the director's decision to give her hardly any screen time, while French actress Iréne Jacob is routinely lost in translation. The most impressive performances in both films are those of the character of Iago, yet the differences between Michael MacLiammóir and Kenneth Branagh are striking. Irish stage actor MacLiammóir's Iago is a devious misanthrope, who obtains innate pleasure out of Othello's misery.

His motives are not just simply a response to Othello jilting him in favour of Cassio, but also are part of his encompassing baseness. MacLiammóir's Iago is truly sinister and efficacious at every level. Branagh on the hand plays Iago as a saucy, bi-sexual rogue: a devious rapscallion that's part Errol Flynn-part Donald Sutherland. His motives are unclear, as Parker's adapation eliminates much of the play's motivation. Instead, his version becomes more about Iago fashioned as a lewd Venetian prankster with a coded desire for Othello .

Parker's film follows the unoriginal template for cinematic Shakespeare in simply filming characters speaking. This lethargic approach is spiced up by his emphasis on Othello's internalized thought patterns, which detail his vivid erotic imagination. Like the Pied Piper of Hamelin, the bawdy sexuality of Parker's film seems to follow Branagh around every bend. Although Branagh's Iago transmits the dangerous sexual images into Othello's mind, he is responsible for the film's cheekiest laughs, which reveal his sexual orientation: the best of which is a scene in which Iago reluctantly exchanges sex with his wife Emilia for Desdemona's handkerchief.

In Welles' film, this sequence is more classically stolid: an unusual perspective given the flair of Welles' approach. There are several delights to be found within the maelstrom of visual ideas within his Othello. The film's brilliant opening sequence harkens back to Citizen Kane in which a dead Othello is escorted on a bed through the hills of Cyprus. Then like an archetypal Noir, the film then reverts to the past to examine how the crime was committed and what motives were utilized. Despite the jarring nature of his camera movements and editing techniques, Welles is able to insert some wonderful moments into his film.

The most notable of which is the film's famous sequence in which Othello believes he is hearing of Desdemona's unfaithfulness. In Parker's version this scene is shot with Fishburne hiding in a cell to signify the trap which he is already locked in; in Welles' film, the Moor listens to Cassio and Iago talking on a windswept rooftop. With the sounds of seagulls and waves crashing muffling the echoed voices of Cassio and Iago, Welles emphasizes the distorted nature of language. Whereas Parker's Othello has always been trapped via race or mental instability (i.e. epilepsy), Welles' Othello has a degree of choice in the matter: his jealousy provokes his actions and thus his failure to elucidate seals his fate.

Part of this is due to Othello's smitten attitude to Desdemona in Welles' film. While at first we are told that Desdemona gobbled up Othello's tales with "a greedy ear," Cloutier's Desdemona seems to lose her appetite for the Moor once they arrive in Venice. Perhaps this is due to the brief timespan of their courtship, as it now Othello, with ears pressed against a stone wall, who is devouring stories of Desdemona with an equally "greedy ear."

In Welles' filmography, the aura of enchantment and magic is a strong theme in films ranging from F For Fake to Macbeth. Our first image of Othello is dressed in clothing that appears more suitable for a magician than a soldier. Ironically, this first meeting is when Othello is being charged with "enchanting" Desdemona with black magic. Yet, it is arguably Iago who is the true magician in Welles' film: turning the charming General into an automaton through is magical use of words. While Iago poisons the mindsets of the title character in both films, Branagh's Iago appears to be simply fulfilling his duty by exploiting Fishburne's tragic flaw. McLiammóir on the hand is sating his own lust for devilish entertainment by exploiting not only Othello, but a host of other characters such as Roderigo with his knave tongue.

The massacre which finalizes Othello is also completed in dissimilar programs. In Parker's version, Fishburne's engages in a voodoo-like ceremony: a paganistic ritual designed to condemn Desdemona for her actions. In Welles' film, Othello wolfishly hunts down Desdemona in the blackness of night. His reason is not simply to conceal his embarassment, but also intriguingly to not let Desdemona maim the hearts of any other men.

Lying in a funereal position, Cloutier's Desdemona seems resigned to her fate. While Jacob fights to live, Cloutier seems prepared to die. Welles' Othello strives to "put out the light" by placing Desdemona in an eternal sleep. His Othello would not seem out of place in a 1930's Universal horror film in a cavernous castle. Yet, his method of death is a symbolic one: suffocating his new bride in her handkerchief as though it were a white veil in a perverted and destructive marriage.

While Iago's back-stabbing ruckus in Parker's film results in a highly contrived bed of death, Welles' film has Iago wreaking havoc across the island: causing an outburst at a Turkish bath and attacking a defenceless Roderigo under the floorboards. The sheer lack of light in Welles film produces a finale of exquisite beauty; as cell-like imagery cascades across the faces and bodies of those whose fate has been sealed through the sheer evil which enacted it.

* Orson Welles' Othello is available on R2 DVD through Second Sight Home Video. Oliver Parker's version of Othello is available through Turner Home Entertainment

Other Orson Welles Films Reviewed:

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) 9/10

Copyright 2007 8½ Cinematheque

Labels: Parker, Second Sight, Turner, Welles

<< Home