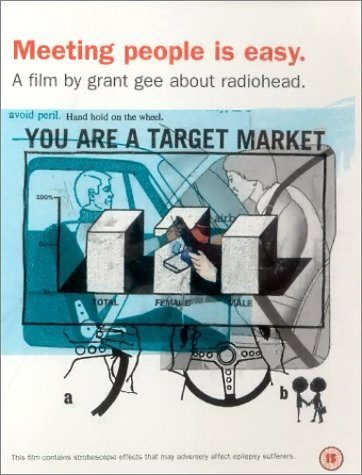

1999: Meeting People Is Easy

Meeting People Is Easy (1999, Gee) 7/10

"I wish I was special..." (Thom Yorke singing "Creep")

"I wish I was special..." (Thom Yorke singing "Creep")"...You are special Thom!" (Audience Member)

"Hey, Radiohead. Creep. Dickhead" (Anoynmous Man on the Street to Thom Yorke)

In 1997, Oxford-based alternative rock band Radiohead released their third album O.K. Computer to massive critical and commercial acclaim. With its loosely conceptual musings about modernization and alienation, the record became the soundtrack to a generation of followers: inspiring a queue of bands in the process such as Coldplay and Muse who fashioned their careers on replicating Radiohead's shimmering fusion of feedback and melody.

Prior to the release of O.K. Computer, the band had released a cult hit single in "Creep" and a classic angst-ridden sophomore album in 1995's The Bends. Had the band fizzled out in 1995, their status as a respectable Nineties band would have been cemented. Instead in a world still processing the popularization of technologies such as the internet, Radiohead's visceral fusion of The Pixies and the Smiths struck a chord with millions upon the release of an album that became its generation's equivalent of Sgt Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band or Dark Side Of The Moon.

On the successive world tour to promote O.K. Computer , Radiohead brought along music video director Grant Gee to capture the daily activities of life on the road with the most hyped band of the late Nineties. Traversing the globe from the first show in Barcelona to the last in New York, Gee follows the band on their 100+ date world tour. The result is a moody documentary showing the negative aspects of fame and the disenchanting elements of modern commercialized music.

While the fabled rock and roll tours of luminaries such as Led Zeppelin were trademarked for their excessive boozing, endless groupies and tattered hotel rooms, the modern tour as shown in Gee's documentary is less about bringing the band to their worldwide fanbase and more about commercialization, public relations and marketing. Working on a rigid schedule, the band entertain an international assortment of journalists, photographers and radio deejay: answering an endless stream of tedious and repetitive questions about lyrics, influences, opinions and so forth.

Evidently for some in the band the flashbulbs, Latvian radio plugs and quizzical soirees become too much. The band's lanky guitarist Jonny Greenwood refuses to do television interviews, frontman Thom Yorke avoids aftershow parties and drummer Phil Selway shuns Gee's camera. This leaves the burden of the interviews on the shoulders of erudite bassist Colin Greenwood and affable guitar Ed O'Brien. While O'Brien is charming and comfortable in providing interviewers with desirable answers and Greenwood conducts interviews in French, the strain of the constant barrage of questioning begins to take its toll.

By the time the band arrive at the tour's 60th stop in Berlin, the sensitive nerves of an exhausted Colin Greenwood reach a psychological crescendo. After telling a visiting English journalist about how much he used to enjoy doing interviews, Greenwood breaks down into near tears: only to quickly pull himself to together and apologize for such seemingly inane frustrations as not being allotted time to tour Berlin. Amazingly, despite Greenwood's obvious fatigue, the next time we see him is with O'Brien and Selway as the trio are whisked off to London via a private jet to attend a meaningless awards show. Ironically, Radiohead's rhythm section are then flown back to Sweden to participate in the band's next concert in Stockholm.

But it is not only during interviews that Gee's camera captures the inner turmoil of some band members. In Germany, Yorke bemoans onstage that he too never got the chance to visit Berlin, but approximately twenty-five shows earlier his apathy towards the tour is plainly obvious. Performing in Philadelphia, Yorke purposely peforms the band's U.S. hit single "Creep" with sneering contempt: even going so far as to holding the microphone while the audience sing.

Much of Yorke's condescension erupts from the band's headlining performance at Glastonbury. In a point, Yorke repeatedly brings up throughout the film, he remembers how he asked the stage manager to turn on the lights: only to reveal to Yorke's horror 40,000 people standing in a field. He tells one journalist that what the sight of this provoked "wasn't a human feeling", but certainly his emotional response afterwards earmarks this moment as the point in which Yorke realizes the magnitude and consequences of fame.

As the tour progresses this theme of disenchantment with stardom becomes more acidic and more overt. The face of the band, Yorke becomes increasingly irritable and depressed as the tour further evades English soil. Gee (over)uses footage of neon-lit streets, moving S-Bahn trains and concrete buildings to capture the isolation and mechanization of modernity, which he proposes in his visual thesis ultimately reflects his morose subject matter. In the Far East, Yorke implodes while talking with the meek Jonny Greenwood. Using Glastonbury as a reference point, we see his bitter opinions of fame: all of which he claims is "just a headfuck." Realizing the nature of stardom, Yorke stubbornly engages in interviews were he despondently nullifies any sign of future music from the band and becomes increasingly political and anti-corporate in his dialogue.

This almost ironic anti-corporate stance from one of the biggest band's on the planet is not solely felt by Yorke. Both he and Ed O'Brien muse with distaste about the staleness of modern rock music and American radio which they presciently acknowlege serves the benefit of advertisers and conglomerates rather than the audience. Gee also uses clips of newspapers to show the absurdities of the modern world. In one newspaper, there is a giant multi-page spread with the band, despite the fact that, as a smaller article notes, the crew of the embattled Mir Space Station are lacking oxygen.

One of the most notable insights of Gee's film is the concept of affection. While the band are adored and receive countless awards, they appear lonely and vulnerable in their isolated hotel rooms and airport lounges. This is an aspect of the rock n' roll lifestyle, which is rarely explored and Gee broadly explores this topic through montage and the moody spectre of personal discontent within the band. When one Australian journalist asks Jonny Greenwood about a critical backlash, he reminds the journalist that it is negative aspects of reviews that stick with the musicians.

The subsequent backlash Radiohead obtains via mainstream morning shows and newspapers proclaiming the band's music as something "to slit your wrists to" is combined with the band's internalized backlash towards fame, or at least the downsides of fame. After spending a year drowning in an international fishbowl, one wonders if all Yorke and the rest of the band truly desires is "a life with no alarms and no surprises." While Gee tries to posit the film as a rebuke to the wild and positive stereotypes of rock and roll, his subject matter and approach somewhat weaken his stance.

For starters the intellectualized and introverted nature of Radiohead inhibits the likelihood that Gee's film would capture the band in the throes of cocaine binges and clutching bottles of Jack Daniels. Instead, we see a band using whatever free time they have to record music; although somewhat ironically the majority of the songs performed and recorded by the band during Meeting People Is Easy never made into onto subsequent albums in their documented form. Secondly, as noted by Yorke and Jonny Greenwood's tendency to shun interviews and events, the band's intense fame does not require them to conduct asinine radio spots and interviews.

Furthermore, for all of Gee's biased emphasis on the negatives of touring, he does show a band who at least the beginning seems quite eager to collect platinum records and receive accolades; until their collective consciences kick in and they begin to question the effects of fame. In an earlier sequence, Yorke blithely informs a journalist that he and the band are aware that they one of those groups, who like The Smiths and REM before them, who effect an entire generation. By the end of Meeting People Is Easy, Yorke begins to become overwhelmed by the pressures of this earlier statement: criticizing the manner to which fame changes individuals and artists, who refuse to artistically evolve in order to preserve their lifestyle.

In 1967, D.A. Pennebaker released arguably the cinema's most famous "rockumentary," as he followed Bob Dylan on his 1965 pre-electric tour of England. One can see similarities between Pennebaker's earlier film and Gee's Meeting People Is Easy: both capture a world famous act in an intimate fashion and interestingly both films document each respective group prior to their shift toward a less popular style of music.

But while Dylan was charged with being a "sell out," Radiohead did the complete opposite: moving away from guitar-based music and more towards less commercialized avant-garde electronica. Additionally, given the band's costly decision to subsequently break future tours into smaller stretches, it is fair to say that the world tour filmed by Gee is in hindsight a document outlining the reasons why Radiohead went from garnering the unlikely and unwanted title of "saviours of rock n' roll" to resclusive rock act in under half a decade.

* Meeting People Is Easy is available on Capitol Home Video

Copyright 2007 8½ Cinematheque

<< Home