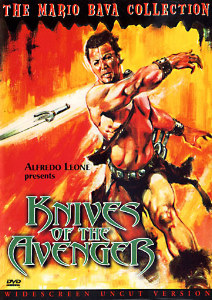

1966: Knives Of The Avenger

Knives Of The Avenger (Bava, 1966) 2/10

The "Viking Epic" is a strand of the "swords and sandals" genre popular amongst audiences in the 1950's. Finding its mainstream Hollywood roots in Richard Fleischer's 1958 Kirk Douglas vehicle The Vikings, the sub-genre spawned a variety of imitators through to the late Sixties.

The "Viking Epic" is a strand of the "swords and sandals" genre popular amongst audiences in the 1950's. Finding its mainstream Hollywood roots in Richard Fleischer's 1958 Kirk Douglas vehicle The Vikings, the sub-genre spawned a variety of imitators through to the late Sixties. Films such as famed British cinematographer Jack Cardiff's The Long Ships and Clive Donner's Alfred the Great were lesser efforts backed by major studios. And although the sub-genre made a brief comeback in the mid-1980s with Paul Verhoeven's Flesh + Blood, its most lasting popularity was found in continental Europe, particularly in Italy. Italian horror director Mario Bava produced two notable European B-Viking films starring American ex-patriate Cameron Mitchell, 1961's Erik the Conquerer and 1966's Knives of the Avenger.

Produced under the Italian title I Coltetti Del Vendicatore, Knives of the Avenger was a troubled production, which Bava attempted to rescue early on through a complete re-write and six additional days of shooting. Often referred to as an Italian version of George Stevens' Shane, Knives of the Avenger is essentially a Spaghetti Western dressed in 8th century period clothing.

Utilizing an unusually complex episodic narrative, Knives of the Avenger follows a presumably widowed Viking woman named Karin (Elissa Pechelli) who along with her son Moki (Luciano Pollentin) goes into hiding from Hagen (Fausto Tozzi): a vicious warrior lusting for Karin's hand in marriage. Believing her husband is still alive, Karin resists Hagen's wrath by hiding with her son in a rural plain. When Hagen's henchmen locate them, she is saved by a passing warrior named Rurik (Cameron Mitchell), whose path has previously interlocked with the exiled family.

More of a character study, than an action film Knives of the Avenger is ultimately a curiosty piece. Replace the film's Scandinavian characters' knives with guns and fur-lined clothing with leather and the film is essentially a western. Disputes and interactions often take place in quasi-saloons, while outlaws roam the countryside .Even Marcello Gombini's score is more fitting of the rural surroundings of the Western than the pomposity of an epic.

Despite being more or less a belated director-for-hire for Knives of the Avenger, Bava imbues the film with a strong sense of his thematic concerns about family relationships and deception. With her family disintegrated by tragedy, Karin aims to protect her son and keep the future of their isolated kinship alive. The well-being of her son and the desire to find her long presumed dead husband are the only instinctual feelings Karin is truly aware of in her maternalistic view on life. Although fearful of the mysterious Rurik's arrival, Karin learns to see him as a protector: a surrogate father figure for Moki.

It is here that the film's comparisons to Shane are most likely arrived at. Like in Shane, an enigmatic figure arrives to protect a family with limited explanation as to why. Alan Ladd's arrival and reasons for aiding a small community are less peripheral to Stevens' film than Rurik's presence in Knives of the Avenger. As with the title character in Shane, Rurik aids in the educational development of the child in the methods required to survival and operate as a man. But in Stevens' film, the mysterious figure also aids in defining the masculine roles of Van Heflin's impotent and weak masculine figure.

Rurik does not engage in such methods in Knives of the Avenger due to the father's absence. Instead he teaches the son life lessons on how to eventually fufill his father's promise. Furthermore, Rurik's motives for aiding the family are more clearly defined. Through an interesting flashback sequence, we see how Rurik's earlier lust for revenge resulted in the defilement of Karin and her former community.

Upon learning of the misinterpreted and deceived past, Rurik feels guilt for his previous actions and thus tries to redeem himself through helping the family. As noted in the flashback sequence, Hagen's earlier deception produced agonizing destruction for countless innocent parties and it is through nullfying Hagen's malevolent tactics that Rurik can compensate for his earlier sins as a rapist and mauradering pillager.

What truly distinguishes Knives of the Avenger from similar films of its era is found in Bava's peculiar cinematography and locations. Characters are often filmed in the foreground to illustrate the feelings of others in the same scene. Often filmed on rolling hills or along sandy coastlines, the director presents a stark contrast between the windswept intensity of the beach and the bucolic tranquility of the hills. Yet, Bava deceives his audience by inverting the meanings of these environments. Through a soothsayer on the beach, Karin acquires an aura of calm, which is almost erased through the aggressive methods used by Hagen's followers.

Despite its unique construction and Bava's reputation as a master visualist, Knives of the Avengers curiously suffers from static pacing and bland aesthetics. The makeshift brown tones add stagnation rather than diversity to Bava's palette, while the emphasis on character study produces a snail-like conundrum in which movement is sacrificed to address the psychological aspects of this medieval revival of the biblical epiphany story: a narrative in which good paradoxically coincides with evil.

This sense of biblical tragedy is never fully realized in Knives of the Avenger. The film's moral implications and complex psychology are weighed down by the dull language and secondary performances. There is arguably potential for a highly interesting film with ethical dilemmas similar to those proposed in Ingmar Bergman's The Virgin Spring, or even Kurosawa's Yojimbo within the material. Ultimately, Bava's inability to cohesively rein in the narrative under a more vibrant tone produces a rather dour and maudlin piece: an appealing investigation of human nature that sadly stupors into mediocrity.

* Knives of the Avenger is available in Anchor Bay's Mario Bava Collection V1.

Other Mario Bava Films Reviewed:

Black Sunday (1960) 9/10

The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1962) 6/10

Black Sabbath (1963) 7/10

Copyright 2007 8½ Cinematheque

Labels: Anchor Bay, Bava

<< Home