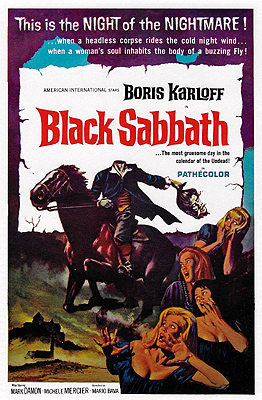

1963: Black Sabbath

Black Sabbath (Bava, 1963) 7/10

Three years after the worldwide success of Black Sunday, Italian director Mario Bava was offered a unique project. In the deal, horror legend Boris Karloff, whose career was once again on the rise thanks to Roger Corman's Edgar Allan Poe adaptations for AIP, was signed for a package deal in which Bava could create a European anthology film similar to Corman's 1962 Edgar Allan Poe triptych, Tales of Terror.

Three years after the worldwide success of Black Sunday, Italian director Mario Bava was offered a unique project. In the deal, horror legend Boris Karloff, whose career was once again on the rise thanks to Roger Corman's Edgar Allan Poe adaptations for AIP, was signed for a package deal in which Bava could create a European anthology film similar to Corman's 1962 Edgar Allan Poe triptych, Tales of Terror.The result was 1963's Tre Volti delle Paure ( The Three Faces of Terror): a trio of short films based on stories by Guy Du Maupassant, Alexei (not Leo) Tolstoi and Anton Chekov. Released in North America under the title Black Sabbath, the films demonstrated Bava's unique visual flair and thematic interests in deception, frayed relationships and betrayal.

One of the more interesting investigations performed by film historians centers on the film's source material. As with Black Sunday, Bava based his film from work written by a well-respected author in Nikolai Gogol's The Vij. Yet, historians have debated whether either Chekov, Tolstoy or Du Maupassant ever wrote any stories similar to those they are credited for in this picture: leading to speculation the author's names were selected for the purpose of adding further refinement to Bava's often pictureseque aesthetics.

Featuring an introduction and amusing coda by Karloff, Black Sabbath opens with The Telephone: a short film supposedly adapted from a story by Guy Du Maupassant. Set in a modish apartment, the film belongs to the uniquely Italian genre of the giallo. Originally based on German Krimis (thrillers), giallo films came into prominence in the mid-Sixties once directors such as Mario Bava, Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci began to infuse heavy doses of rich colour and visual flamboyance into these tawdry crime stories. A pre-cursor to the modern "slasher film," giallo were noted for their overt eroticism and sadistic violence.

In The Telephone a woman (Michele Mercier) repeatedly receives phone calls from a caller claiming to be her now-jailed ex-boyfriend who has escaped jail to seek revenge upon her. With its detailed information from a watchful caller, the film is an obvious influence for Wes Craven's 1996 horror parody Scream. However, within its savage red telephone, one could argue that Bava is providing his own tongue-in-cheek response to the fluffy "white telephone" films that dominated Italian cinema during the reign of Mussolini.

The second film is taken from a story by Soviet writer Alexei Tolstoi entitled The Wurdulak, in which a young Russian aristocrat Vladimir (Mark Damon) comes into contact with an isolated family whose aging patriarch (Boris Karloff) has ventured off his property to kill a Wurdulak- an undead vampire similar to the characters in Bava's Black Sunday- only to become one himself. The third film entitled A Drop of Water involves a rude nurse who is summoned on a stormy night to the home of her deceased patient to prepare her body for burial. Believing she will not be paid, she steals the deceased woman's ring, only for the latter to visit her from beyond the grave.

When released by AIP in 1963, Black Sabbath was severely censored and re-arranged by AIP due to the film's explicit sub-text and graphic imagery. In the original Italian version of the film A Drop of Water featured last in the proceedings, while the AIP edit moved this story first, followed by an re-edited version of The Telephone and then the Karloff short The Wurdulak. Current editions of the film released by Anchor Bay use the superior European version with its chilling violence and explicit sub-text.

Upon its initial North American release, The Telephone in particular was scythed by editors due to is overt lesbian content. In the AIP versionm, the homosexual allusions were removed and replaced by a half-baked notion of a ghost haunting Michelle Mercier's character. While other films of the era, most notably William Wyler's 1961 film The Children's Hour and Robert Wise's 1963 film The Haunting contain sub-textual allusions to lesbianism, Bava's short film was groundbreaking in its nature. In the film, Michelle Mercier's character Rosy believes her ex-boyfriend is stalking her on the telephone, the story takes an unexpected shift as Bava reveals the speaker to be her friend Mary (Lidia Alfonsi). Muffling her voice using a cloth, Mary is able to convince Rosy she is a man.

This subversion of gender roles is interesting as it posits Mary as the masculine element in this homosexual relationship. According to Mary, the relationship was destroyed by Rosy because of her boyfriend. Thus, Rosy attempts to restore the balance through revenge on Mary. The sub-text becomes extremely interesting once Mary enters the apartment and attempts to appease Rosy's fears by offering to sleep in the same bed with her. After Mary obtains a nightgown, Bava pans to a window to demonstrate the shift in time: only to follow it with a lurid jazz soundtrack and Mary commenting on the night before.

Mary's sexuality is one of the many instances of deception in Black Sunday. As in Black Sunday deception and betrayal come from unlikely sources. Rosy expects her former boyfriend to be out for revenge, but unknowingly lures the real attacker into her apartment in the form of another former lover. Such is her comfort around Mary, Rosy even is not perturbed when the former decides to plant a knife under her pillow.

In The Wurdulak, Karloff's aging patriarch convinces his family, he has not been turned into a Wurdulak: only for him to deceive them in the night. In a scene similar to the infamous "corpse kiss" in Black Sunday, Vladimir is falsely seduced by the patriarch's daughter Sdenka (Susy Andersen) through her hypnotic eyes. In One Drop of Water, the angry nurse summizes to procure her former patient's ring as payment for arousing her services on a dreadful night. Yet, this deception fails as the deceased clairvoyant seeks her revenge through alternative methods.

This deception also brings forth ideas of destiny. As with Black Sunday, the short films in Black Sabbath feature notions of celestial fulfillment. In The Wurdulak Sdenka informs Vladimir her destiny is to suffer at the hands of her family. Like in Black Sunday, future generations are expected to fulfill the payment of the errors and misdeeds undertaken by their ancestors or elders. In One Drop of Water, the former patient seeks out her revenge through restoring the supernatural equilibrium.

Crypts and chapels are also utilized with a degree of complexity in Black Sabbath. In Black Sunday, the tattered chapel houses a crypt filled with evil. Only a monolithic stone cross is able to provide a degree of safety and sanctuary for its visitors. In the cobwebbed lair in Black Sabbath this stereotypical notion of sanctuary in a holy building is manipulated by Bava. Despite her fears, Vladimir informs Sdenka that they will be safe in the family crypt. Yet, in this dank building lacking in religious artefacts or paraphernalia, supernatural evil is allowed to subsist and thus the pureness associated with Judeo-Christian burial grounds is broken.

All three films demonstrate Bava's thematic interest in the disruption of relationships. In The Wurdulak, the patriarch's family is destroyed through his evil, yet they are re-united through a heinous sense of familial kinship. One Drop of Water illustrates the fissured trust between medic and patient, while in The Telephone a former lover seeks revenge due to the collapse of a previous relationship. In all three films, the guilty party is punished; yet there is not necessarily a restoration of earthly balance: the film even alludes to the possibility of further revenge in at least one of the stories.

One of the major criticisms regarding Black Sabbath is the thinness of each story's plot. None of the stories are particularly gripping on a pure narrative level. As with Black Sunday, Bava's emphasis on filmic utilities such as sound and cinematography imbue the stories with a decadent sense of accomplishment. In The Wurdulak's snow-covered Gothic forests and cobwebbed chapels, one can visualize how Black Sunday would have appeared had it been in colour.

With its lush matte paintings, twisted sets and fantastic use of colour, Bava's film anticipates the type of unsettling and atmospheric horror that Japanese director and fellow former painter Masaki Kobayashi would perfect in his 1964 Winner of the Cannes Special Jury Prize entitled Kwaidan: a film which also utilizes an anthology format, but whose subject matter is told strictly within a period setting and is taken from one source in Lafcadio Hearn's collection of Japanese folk-tales .

Surprisingly Black Sabbath was the first of Bava's horror films to be shot in colour: he had already directed two low-budget Italian historical epics in colour prior to Black Sabbath. The addition of colour eliminates much of the enigmatic elements of suspense from Black Sabbath, although it is arguably used with brilliance, particularly in One Drop of Water and The Wurdulak. In The Wurdulak one can already see the seeds for Tim Burton's Sleepy Hollow with its melancholy trees and rustic surroundings.

Visual imagery is paramount to Black Sabbath. The film's most memorable sequences occur through carefully plotted aesthetic approaches that unlike in Black Sunday are also able to beautifully incorporate sound for a horrific orchestration upon the senses. Although not shown on camera, Karloff's destruction of his grandson is particularly shocking for the era. The infant's phantom crying for his mother to let him from the cold is both heartbreaking and chilling in Bava's skillful abilty to blend the sound of the wind and a young boy.

In One Drop of Water, the director applies the concept of Chinese Water Torture to an aural setting in having his culprit become insane through hearing the mere sound of water. However, it is the hideous corpse which is easily the segment's most memorable device: twisted, frayed and mutilated in its own skeletal satisfaction. Despite its rigid nature, the corpse is easily one of the most spine-tingling elements of the film and could possibly be seen as an ode to Hitchcock's Psycho.

In Black Sabbath Mario Bava delievers a curious atmospheric blend of terrific visual scares. Although the stories are lacking in their narrative construction, the visuals are beautifully arranged and filmed in classic giallo and gothic style. Analyzed separately, the three films are compositions in specific styles of horror ranging from the thriller to the period piece to the realm of the supernatural. While they may not always work in terms of plot, they are astute exercise styles in style and composure. The performances, particularly from Karloff are solid, while Roberto Nicolosi's score along with Ubaldo Terzano's cinematography and Giorgio Giovanini's art direction are particularly menacing.

* Black Sabbath is available in Anchor Bay's Mario Bava Collection Vol 1

Other Mario Bava Films Reviewed:

Black Sunday (1960) 9/10

The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1962) 6/10

Knives of the Avenger (1966) 2/10

Copyright 2007 8½ Cinematheque

Labels: Anchor Bay, Bava, Italian

<< Home