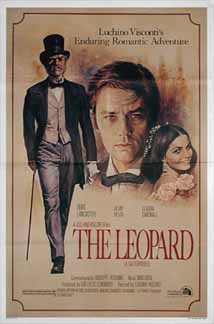

1963: The Leopard

The Leopard (1963, Visconti) 10/10

"We were the leopards, the lions, those who will take our place will be jackals and sheep, and the whole lot of us- leopards, lions, jackals and sheep- will continue to think ourselves the salt of the earth" (Prince Don Fabrizio Salina)

"We were the leopards, the lions, those who will take our place will be jackals and sheep, and the whole lot of us- leopards, lions, jackals and sheep- will continue to think ourselves the salt of the earth" (Prince Don Fabrizio Salina)The Leopard is a film about the ascension of one class and the decension of another. Set in the mid-19th century, the film explores the uprooting of traditional Italian society as a result of the cultural and political movement of the Risorgmento (or resurgance). In the decades following the defeat of Napoleonic Europe, the age of empire was unknowingly on the wane. The liberation of communities from imperial forces and the rise of romanticism in fractured "nations" sparked desires for statehood and the unity of a people.

Alongside the German "nation", the Italian people were a group desperate to bring a political unity to their separate kingdoms and myriad of city-states which composed the Italian nation in order to create a single Italian state. This resurgance in Italian national identity after generations of foreign conquest had troubling consequences for tradtional Italian society. The country was split over the political identity of this new state as a constitutional monarchy, a confederation under the leadership of the Vatican or a democratic republic. It is within this historical context that The Leopard takes place in which the ancien riche and nouveau riche jostled for the leadership and power of this new Italian nation-state. The film's title is most likely taken from an Italian term "Gatopardismo" (the term awkwardly translates into English as Leopardism) when according to historian Tony Judt individuals change their political "spots" or affiliations in order to avoid conflict in changing political situations.

The Leopard is set around the activities of aging Prince Don Fabrizio Salina (Burt Lancaster) on the island of Sicily over a two year period. The Prince is an erudite scientific scholar, a man of logic who is prided around the island for his feats in the realm of astronomy. A commanding and intelligent patriarchal figure, the Prince's interior domestic life is opposite to his exterior regal status. The film's opening shots lead us to a grand country mansion located within the harsh Sicilian landscape: embodying the splendour and opulence the Prince manifests in his exterior life against the harsh terrain with its own political symbolism. Inside, the family are holding mass despite the cries of the servants who find a young soldier dead on their property. The revolution has hit home. Along with his priest, he decides to travel to a different home in order to protect it from the marauding soldiers of Garibaldi's republican Red Shirts who have landed in Sicily. The decision to bring along the priest is more a matter of protection, rather than spiritual advisement as throughout the film traditional institutional figures such as priests are showed great reverance and respect. While the rest of his family sob over the Prince's dangerous trip, he vents his disgust and anger to them. This early scene shows us a key facet to the Prince's personality in relationship to his family members.

The Leopard is set around the activities of aging Prince Don Fabrizio Salina (Burt Lancaster) on the island of Sicily over a two year period. The Prince is an erudite scientific scholar, a man of logic who is prided around the island for his feats in the realm of astronomy. A commanding and intelligent patriarchal figure, the Prince's interior domestic life is opposite to his exterior regal status. The film's opening shots lead us to a grand country mansion located within the harsh Sicilian landscape: embodying the splendour and opulence the Prince manifests in his exterior life against the harsh terrain with its own political symbolism. Inside, the family are holding mass despite the cries of the servants who find a young soldier dead on their property. The revolution has hit home. Along with his priest, he decides to travel to a different home in order to protect it from the marauding soldiers of Garibaldi's republican Red Shirts who have landed in Sicily. The decision to bring along the priest is more a matter of protection, rather than spiritual advisement as throughout the film traditional institutional figures such as priests are showed great reverance and respect. While the rest of his family sob over the Prince's dangerous trip, he vents his disgust and anger to them. This early scene shows us a key facet to the Prince's personality in relationship to his family members.He is a loner amongst them: an isolated figure who ignores his plain daughters and directionless son. He no longer engages in sexual activities with his wife Maria Stella (Rina Morrelli), but rather spends time with a lower class prostitute in the ghettos of Palermo. With his power and prestige, the Prince can even disregard the spiritual advice from the family's bumbling Catholic priest without much complaint. Whilst filling the air with blunt anti-clerical jokes and quips to his uptight clergyman, the two individuals whom the Prince is most direct and honest toward are his hunting partner Don Francisco Ciccio Tumeo (Serge Reggiani) and his politically agile nephew Tancredi (Alain Delon).

The first time we see Tancredi is in the reflection of a mirror while the Prince is shaving. In Tancredi, the Prince not only sees a younger version of himself, but the key to securing the family's future and prominent status in Sicilian society. His love for Tancredi is so strong that when his nephew rejects the Prince's shy and stubborn daughter Concetta (Lucilla Morlacchi) for a local middle-class Mayor's daughter Angelica (Claudia Cardinale), the Prince supports Tancredi against the wishes of his wife. Tancredi needs the financial security that the newly-bourgeois Mayor Don Calogero Sedara (Paolo Stoppa) can provide in exchange for the false sense of privileged influence that only the old aristocratic nobility can offer as compensation. Furthermore, Tancredi is an opportunistic and free-spending individual who unlike the prince acts on impulse rather than calculated logic. With little faith in the abilities of his own son, the Prince places his trust, adoration and reputation in Tancredi who has joined Garibaldi's anti-aristocratic Republican Red Shirts under the pretense that "If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change."

The first time we see Tancredi is in the reflection of a mirror while the Prince is shaving. In Tancredi, the Prince not only sees a younger version of himself, but the key to securing the family's future and prominent status in Sicilian society. His love for Tancredi is so strong that when his nephew rejects the Prince's shy and stubborn daughter Concetta (Lucilla Morlacchi) for a local middle-class Mayor's daughter Angelica (Claudia Cardinale), the Prince supports Tancredi against the wishes of his wife. Tancredi needs the financial security that the newly-bourgeois Mayor Don Calogero Sedara (Paolo Stoppa) can provide in exchange for the false sense of privileged influence that only the old aristocratic nobility can offer as compensation. Furthermore, Tancredi is an opportunistic and free-spending individual who unlike the prince acts on impulse rather than calculated logic. With little faith in the abilities of his own son, the Prince places his trust, adoration and reputation in Tancredi who has joined Garibaldi's anti-aristocratic Republican Red Shirts under the pretense that "If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change." A key feature of The Leopard is in Mario Serandrei's smooth editing which allows the film to flow at a brisk pace and allows for the seemless transistions between the intimate and the operatic. Like the Prince's favoured astronomical sciences, Visconti's film utilizes a cyclical notion of history. Characters, words, actions and events are re-simulated in subtle disguises to address the changing nature of Italian society and the Prince's domestic life. This is notably seen through the actions of Tancredi, particularly when he is shown acquainting with the ever-changing Italian military, as they quickly move from being Garibaldi's impulsive anti-royalist guerilla forces to regimented pro-royalist anti-terror squads. The infusion of democratic ideals onto the Sicilian political landscape with a plebiscite regarding the annexation of Sicily to the Italian mainland is another key matter in demonstrating the modifications of class relationships and the influx of corrupt political schemes including bribery, rigged elections and the acquistion of tracts of land through backhand tactics.

[Spoilers in the the next two paragraphs]

The Leopard may be an Italian film, but it is a Sicilian epic. The island's harsh topography, inclimate geography and impoverished status is used to great effect throughout Visconti's intelligent epic. The loss of an independent Sicilian political identity is a key element to the picture, which is mostly felt on the shoulders of Lancaster's Prince. Despite his initial happiness with political unification as a means of securing his own future, the Prince becomes increasingly dismayed at the underhand approach and dirty tactics displayed by the local bourgeoisie, the military and the federal Italian politicians. The film can be viewed as one of two parts: the first in which Italian annexation is seen as a route to secure prosperity through Tancredi and the second in which the Prince realizes the utter failure of such an approach that has done little to protect his prominent status. As with other films in the period, The Leopard is equally a film about the conflicts between the old and the new. On a political level, this can be seen in the Prince's arguments with the bourgeoisie; on a domestic level it is through his fleeting faith in an increasingly bawdy and comtemptuous Tancredi and his realization of the defiencies of his own youthful progeny.

The film's celebrated ballroom sequence- beautifully shot by Giuseppe Rotunno- demonstrates the Prince's melancholic summarization of his choices were the generations of cross-breeding between select families and cousins has not resulted in a purified and noble class, but rather a slovenly and ignoble group of idle children who are either overtly wayward in their direction or stubbornly refuse to have any such as his own daughter Concetta who refuses the overtures of a Milanese Count (Terence Hill) due to her distaste for the urban north and her dwelling upon a lost love. Here the politically young rebuke the ideas of their elders without apology or reservations; while the youthful children dance and giggle only for their parents to attempt securing partnerships to save their fading status. Thus it is only through a last waltz with his beloved nephew's fiancee Angelica that the Prince realizes his own failures and triumphs: finding solace in angelic beauty.

Throughout the film Visconti rarely uses close-ups; preferring instead to utilize medium and long-shots to enhance the interior mood of the character against the architecture: a method utilized by both Antonioni in L'Avventura and Olmi in I, Fidanzati. The ballroom sequence is one of several sequences that uses the motif of multiple doorways being opened at once noting the opportunites and pathways for the characters to choose. Visconti's method, whether in elegant salons or dim alleys, to allow characters to fade out of view is another remarkable visual symbol designed to show the impermenant status of mortality and livelihood.

Unlike American epics of the period, Visconti allows Rotunno's camera to blend into the crowd as almost a third-party observer: gazing upon the characters in question from eye-level as by-passers naturally walk in-front of their field of view. The stunning cinematogrpahy ranges from the impressionistic influenced exterior imagery which evokes the cruel majestic status of nature, to the Baroque interior sequences which are ornately decorated, lavishly costumed and exqusitely detailed. The rich cinematography provides a deeper layering of the character's thoughts and feelings: aiding in the film's visual psychology.

Despite belonging to an ancient Italian aristocratic family himself, Visconti was an intellectual Marxist who preferred on paper the idea of egalitarianism. Thus, the director has a personal equation to the film's themes of a vanishing class, as well as the Prince's own struggle with balancing democracy and the retaining of his former privileged status. Visconti's use of locations and ability to allow characters, images and feelings to engage in a transition between detachment and intimacy is a rare feat in a historical epic. Nina Rota's score adds the atmospheric notions of melancholy and prestige in its richness. In one of his best roles Lancaster is strong and powerful as the tempermental, yet unenduring noble figure who labours to balance authority and change. Delon is magnificent as the Prince's spontaneous playboy nephew adding a degree of envy and ill-boding motivation to the character. Yet, the real star here is Cardinale: a gorgeous ball of steaming sex, who perfectly fits into the naive aura of her character as an individual who brightens weary hearts and stops the activities in the room with a single movement.

The Leopard is a brisk, scholarly and gorgeous historical epic. Shot with decadent care, the film manages to encompass the chameleon-like changes in tone set in motion by the events of the Risorgmento in mid-19th century Sicily. With a splendid cast, Visconti captures a moment in time that whilst predating the political changes of the late Sixties feels to be an ominent forecaster of the failure of such revolutionary ideas. The setting of Risorgmeneto Italy was utilized by Visconti in earlier pictures such as Senso and therefore it would have been interesting to see how similar Visconti would have made this film in 1968, rather than 1963. Such is its universal classicism and inquisitive political approach, it is unlikely he would have changed a single beautiful thing.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

* I would advise anybody who wishes to see The Leopard, but has no background in Modern European history to watch the fifteen minute historical context special feature on the second disc about the Risorgmento on the Criterion DVD prior to watching the film. It does not give away any spoilers and is a valuable aid for those without any knowledge of that period.

** The Leopard is available through Criterion

Copyright 2006 8 ½ Cinematheque.

<< Home