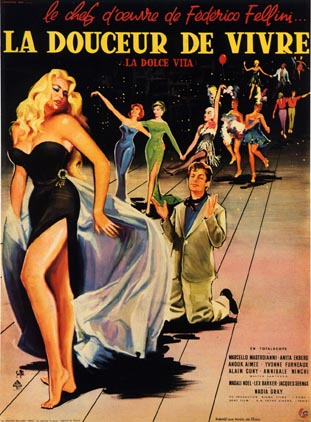

1960: La Dolce Vita

La Dolce Vita (Fellini, 1960) 10/10

La Dolce Vita (Fellini, 1960) 10/10In my early cinematic education there were three crucial films to my initial development and understanding of the medium: (1) Cameron Crowe's 2000 coming-of-age film Almost Famous (2) Francois Truffaut's 1959 debut Les Quatres cents coups (400 Blows) and (3) lastly Federico Fellini's 1960 masterpiece La Dolce Vita.

Whereas Almost Famous and 400 Blows introduced me to what I would later acknowledge as the basic framework of "auteurism" and its autobiographical elements, La Dolce Vita was another matter entirely. A visually striking modern morality play set amongst the glamour and glitz of Rome's affluent Via Veneto, La Dolce Vita introduced myself to the fantastic cinematic indulgences of Federico Fellini.

Prior to co-directing his first film alongside Alberto Lattuada 1951's Luci del Varieta (Variety Lights) Fellini had been one of the finest screenwriters of the neo-realist period: lending his hand to some of Italian neo-realist pioneer Roberto Rosselini's finest films including Rome, Open City, Paisan and The Flowers of St. Francis. The neo-realist emphasis on almost documentary authencity in its locations, plots and performers was at odds with Fellini's own surreal imagery and absurdist sense of humour.

By his fourth full-length film 1954's La Strada, Fellini had grew tired of the artistic restrictions placed upon him by the neorealist ethic.  La Strada could be classified as Fellini's last neo-realist picture and his first "Felliniesque" film as its motif-laden imagery counteracted with the stark reality of the films of de Sica and Rosselini. With 1957's Nights of Cabiria, Fellini had created his own distinct visual identity, which employed his satirical brand of humour and flamboyant imagery as a counterpoint to his investigation into the moral complexity of modern human life.

La Strada could be classified as Fellini's last neo-realist picture and his first "Felliniesque" film as its motif-laden imagery counteracted with the stark reality of the films of de Sica and Rosselini. With 1957's Nights of Cabiria, Fellini had created his own distinct visual identity, which employed his satirical brand of humour and flamboyant imagery as a counterpoint to his investigation into the moral complexity of modern human life.

The follow-up to Nights of Cabiria was 1960's La Dolce Vita: a decadent juxtaposition of modern vices and spiritual emptiness. Although ideas of contemporary moral destitution had been prominently argued in both La Strada and Nights of Cabiria, La Dolce Vita utilized a distinctly modern and urban decor to develop its line of questioning.

Often described as a contemporary reworking of Dante's Divine Comedy, the film is at its core a topical morality play: an allegory of modern society's unquenchable materialism, greed and desire for fame and fortune. Fellini was not the only Italian filmmaker to address such themes during this period. Michaelangelo Antonioni's L'Avventura delves into similar concerns with more a distinctly more ambigious end-product. That's not to say there is not mystery to Fellini's film, as the film's devasting finale embodies a degree of equivocality, but rather Fellini's film is far more cunning in its exploration of deceit: examining a full-range of characters from all classes, ethnicities and social backgrounds.

The film stars Fellini's "alter-ego" Marcello Mastroianni as Marcello a journalist for a Roman tabloid who cruises the streets with his chief photographer Paparazzo (Walter Santesso) looking for the latest star or affluent jet-setter to catch in an adulterous act or making a fool of themselves in public. Despite his desires to enter a more dignified profession as an author or a journalist for a respectable publication, Marcello openly enjoys the social benefits associated with his based brand of journalism.

The film stars Fellini's "alter-ego" Marcello Mastroianni as Marcello a journalist for a Roman tabloid who cruises the streets with his chief photographer Paparazzo (Walter Santesso) looking for the latest star or affluent jet-setter to catch in an adulterous act or making a fool of themselves in public. Despite his desires to enter a more dignified profession as an author or a journalist for a respectable publication, Marcello openly enjoys the social benefits associated with his based brand of journalism.

Although barely middle-class Marcello continues to indulge in the vices and luxuries of the rich. He drives a sporty British convertible, coolly adopts his favourite black shades and sleeps with an attractive socialite Maddalena (Anouk Aimee). Yet, their relationship is not valid within the social confines of the Roman elite and they are forced to discreetly quench their sexual appetites in the flooded basement apartment of a working-class prostitute.

Furthermore, Marcello has recently become smitten with blonde American bombshell Sylvia (Anita Ekberg) who is filming an epic in Italy. Hoping to take advantage of her fractured relationship with her alcoholic boyfriend Robert (Lex Barker), Marcello attempts to woo Sylvia. But Sylvia is not interested. Not because she does not find Marcello attractive, but she too like Marcello suffers from an ability to commit to an idea. Whereas Marcello's failure to commit is in the form of his suicidal girlfriend Emma (Yvonne Furneaux); Sylvia is unable to focus on a single direction. Despite her appearance, she is naive and childlike: buzzing from one idea to the next and fascinated by life's little pleasures from howling wolves, to lost kittens and an evening dip in the Trevi Fountain.

Yet, the film is not solely about Marcello's relationship with women, but rather his (and society's) thematic descent into hell. Here, Fellini equivocates on characters unlike in any film before. As in Nights of Cabiria, the theme of the sacriligious abuse of religious faith is demonstrated. In La Dolce Vita the act is carried out by two seemingly pure and innocent children who cause a media frenzy in a rural Italian village after they claim to have seen the Virgin Mary. Congruently, Marcello's acquaintance and mentor Steiner (Alain Cuny) is stripped of his veneer of intellectual respectability and domesetic bliss. As with the two children, the media once more is viewed as a negative and iniquitous body designed to exploit the feelings and beliefs of ordinary people.

As Marcello increasingly delves into the world of the rich and accepts invitions to particpate in their activities and vices, the more selfish and spiritually corrupt Marcello becomes. Yet, with his lust to attain validity within the "sweet life" of the Roman social elite, Marcello begins to lose all ties to reality and his soul. His life becomes an empty mess as he is outcasted and shunned by his former wealthy friends and lovers: left to drunkenly stumble alone on the beachfront unable to hear or remember the remnants of an incorruptible conscience in the form of a young girl he met at a restaurant earlier in the film.

La Dolce Vita continues to remain as fresh and vigorous today as it was more than forty years ago. An important piece of modern cinema, the film showcases a materialist society similar to our own filled with spiritually bankrupt individuals placating themselves with frivolous luxuries. The acting, direction and atmosphere created by Nino Rota's score and Martelli's cinematography is undeniably cool, but also contextually portent with its omens of moral depravity.

While Fellini's later films such as Juliet of the Spirits and Satyricon would be take on a far more colourful and carnivalesque role, La Dolce Vita is perhaps more grotesque in its character portraits. The authenticity of the characters and those who played them is undoubtedly essential to this legitimacy. Each of the actors appears to genuinely equate with their character: from Anita Ekberg's bouncy Sylvia to Mastroianni's brilliant portrayal of the curiously indecisive Marcello.

In La Dolce Vita, Fellini presents a vision of Rome that is both blissful and poisionous. The high life becomes the forbidden fruit that Marcello voraciously gnaws upon leading to a debauched life of promiscuous adventures that are empty morally, ethically and spiritually. Otello Martelli's voluptuous widescreen cinematography along with Nino Rota's imaginative employment of music ranging from liturgical to rock adds to the multiple identities and conceptions of morality throughout the film. The cavernous club in which Marcello begins to woo Sylvia is fascinating in its hellish decor and satanic maestro Frankie Stout (Alan Dijon), yet Fellini shows throughout the film that locations such as this and the watery flat in which Marcello and Maddalena copulate in are not the only locales of moral depravity.

Less obvious realms such as Steiner's intellectual haven and the rural God-fearing community were the visions of the Virgin Mary take place are also viewed by Fellini to have the ability to allow the corruption of the human soul to occur. Despite the film's ascensions and descensions of locales throughout La Dolce Vita, Fellini repeatedly demonstrates that Hell as a breeding ground for sin and vice is not always recognizable in the film and often takes on new symbolic forms such as the respectable homes of the elite or the glitzy Via Veneto.

Additionally, Marcello's debasement is congruent to his own inability to communicate with those around him. The film's famous opening shot of a statue of Christ carried to the Vatican by a helicopter featuring Marcello emphasizes the modern failure to communicate to others as a significant social flaw, which has resulted in the ability to adopt and maintain dual lives and feelings as seen in the case of Steiner. By the film's end the breakdown in communication between the film's characters has resulted in their complete moral perversion noted by Marcello's inability to hear a young girl along the shore.

* La Dolce Vita is available on R1 DVD from Koch Lorber.

Copyright 2006 8 ½ Cinematheque.

Labels: Fellini, Italian, Koch Lorber, La Dolce Vita, Mastroianni

<< Home